- Get link

- Other Apps

- Get link

- Other Apps

My online storefront, The Magic Nutshell Bookshop, is named for an obscure fairy tale object that has never made it into a Disney movie along with the pumpkin carriages and enchanted slippers. In oral folk traditions of Eurasia, the magic nutshell was a yonic tool of salvation for women in danger that functioned sort of like D&D's "bag of holding." It was small, as the seeds of mighty trees are known to be, but with outsized potential to bring forth many and larger objects of feminine power.

The familiar tales popularized by the Grimm Brothers and further mass-marketed by Disney hail from a set of weird and wild traditions with some narratives rooted thousands of years in the past. These stories are far older than Western pop culture, older than Christianity, older than patriarchy as we know it today. Far from serving as simplistic lessons for well-mannered children, folktales functioned as collective shadow work. Even when the Grimm Brothers began to document oral folktales just a couple hundred years ago, they were still potent with Pagan bloodlines, roiling with motifs of murderous unicorns that had to be culled like pests, hermaphroditic giants with magical breastmilk, men and women who bet the devil and won, science fiction steampunk machine monsters, taboo desires running rampant through the dark woods, the animalistic morality of Norse legends, and a raw tenderness of juicy human feeling that must have felt more naked and obscene than hard sexual impulses to the uptight bougie Victorian-era dads who comprised the Grimm Brothers' target market for book sales.

One of the most fascinating lessons I've learned from studying folk narratives throughout Eurasia and beyond, before the great Grimm edit, is that for every seemingly highly-gendered story such as "Cinderella," there are countless ancient variations with the genders reversed. It became trendy in the late 20th century to come up with cheeky "gender flips" of popular fairy tales as a subversive way to modernize them, but I wish more people knew that these supposed updates are merely weak attempts to reinvent an ancient and well-traveled set of wheels. There have always been cultural beliefs about the differences between men and women and what those differences mean regarding gender roles, but the conversation has evolved considerably with sex and gender beliefs thoroughly dismantled, examined, reassembled, and subverted through time and across cultural boundaries, through the medium of folklore.

My book Leirah and the Wild Man draws from authentic 11th century history and from many of the tangled threads of contemporary folktales and beliefs of the cultures represented in the novel. Main characters Leirah and Aven are based upon the adoptive brother and sister in the heartbreaking tale of abandoned children's fierce love for each other, "Fundevogel," or "Foundling Bird," and as they flee their tragic past in search of their destinies, they drift along parallel paths inspired by "gender twin" variants of the Cinderalla-type tales "Allerleirauh," or "All Fur," and "The Widow's Son" of Norse tradition.

|

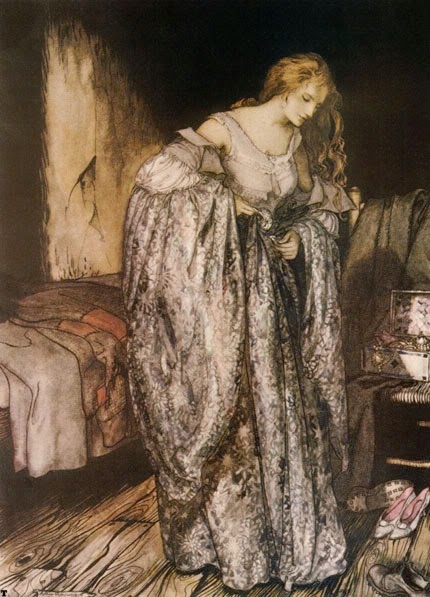

| illustration of Allerleirauh by Arthur Rackham |

I love the magic nutshell because of all the symbolic power it holds in its small, simple form.

It symbolizes femaleness, fertility, and the seed of life. The meat inside of a walnut shell is precious food. Crack the shell in half, and you see a heart inside. Take off the green hull, and you see ink on your hands--ink that was used by many ancient people for writing.

In folklore, there are plenty of stories of magic found or held inside a tree or a part of a tree--a branch, a fruit, a hollow trunk, or a nutshell.

In the 1914 collection of Norse tales illustrated by Kay Nielsen, East of the Sun and West of the Moon: Old Tales from the North, "The Widow's Son" mirrors the story of Allerleirauh, with a hero who is a boy called simply "the Lad."

Instead of a bad widower father, the Lad has a bad widow mother. Allerleirauh runs away because her father wishes to marry her; the Lad's mother kicks him out on the street because she can't afford to feed him. (At least she doesn't try to eat him as some biological fairy tale parents do.)

Instead of a magic nutshell, the Lad keeps his impressive treasures in the phallic trunk of a magic lime tree (not the kind that grows limes--it's a local name for a linden tree).

Allerleirauh and the Lad both set out to work as servants for a royal household, disguised as vagabonds and sleeping under stairs; Allerleirauh wears a patchwork fur hood and soot, while the Lad wears a wig of fir-moss and smears of dirt.

Allerleirauh and the Lad both set out to work as servants for a royal household, disguised as vagabonds and sleeping under stairs; Allerleirauh wears a patchwork fur hood and soot, while the Lad wears a wig of fir-moss and smears of dirt.Both are summoned to the suspicious, opposite-sex king/princess's bedroom on successive nights; Allerleirauh gets boots thrown at her face, while the Lad gets a place to sleep by the doorway.

Both appear three times in their magical garb but run away before the royals can learn their identity; Allerleirauh attends fancy balls in her shining gowns, while the Lad engages in battle wearing shining, beautiful armor. Both are finally discovered by an object placed on their bodies while they are wearing their magical disguises--Allerleirauh by a golden ring slipped onto her finger, the Lad by a handkerchief tied around a leg wound. Both have their lovely hair forcibly uncovered by their respective suspicious royal; Allerleirauh's king throws off her hood, and the Lad's princess orders her maid to yank off his wig while he sleeps.

In both cases, the sight of a healthy head of hair is so seductive that its revelation is quickly followed by a royal wedding.

I love this story and all its densely packed symbolism. It's about growing up and leaving home, the drive and dangerous but life-sustaining force of sexual maturation, separating from one's parents to find a mate, and all the danger and indecision and vulnerability of revealing one's true nature to a romantic partner in due time. In both gender variations, it's the vagrant who initiates contact but the royal who does the pursuing. The visual images in these stories are evocative (even without gorgeous illustrations), and the sensual tension runs high.

Alone, the story of Allerleirauh looks like a tale about an oppressed female character using all of her wits and resources to survive in a male-dominated world. And so it is. But if Allerleirauh shows us how bad it is to be a woman in an oppressive patriarchy, the Widow's Son shows us how much worse it is to be a man in the same context. Because in the world of folktales, filled with gender-reversed variants of every story, it becomes clear that masculinity and femininity were not defined by whether one was the hero or the prize, the brave one or the innocent, the one with the pretty hair or the one who was desperate to see it. Gender was more about tools and trades. Allerleirauh's "battles" are fought in ball gowns, and her tools are household objects. The Lad's finery is armor, and he wears it on an actual battlefield. When Allerleirauh is decorated with a ring, the Lad is festooned with a bandage for his arrow wound. At first glance, it seems that Allerleirauh's love interest treats her worse than the Lad's, but it is his life that is in more danger than hers. Allerleirauh's ill-treatment is more insult than injury--certainly with the implicit threat of worse--but it would not be expected for the king to seriously injure, let alone kill her. However, when the princess brings the Lad into her bedroom to toy with him, she knows with certainty that her father would have him executed if he were discovered there.

If I could choose my weapons, I'd take a ball gown over a suit of armor any day--a pen over a sword, a golden trinket to trade over a spear to throw. I love prettiness, femininity, relative freedom from violence, and the emotional complexity of being a woman. I understand the thrill of wielding physical power, but I'm glad to be a lady. And so I celebrate the quiet power of the magic nutshell.

It is interesting to note that within the supposedly male-privileged patriarchal societies of medieval Europe, life expectancy for men remained stubbornly far lower than life expectancy for women until the supposedly-progressive Renaissance stimulated a backlash of witch hunts, which evened things out via the mass murder of intelligent and competent women.

Special thanks to scholars such as Jack Zipes, who have worked to restore Western culture's lost access to the wild history of the folk traditions behind our collective fantasies.

- Get link

- Other Apps

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment